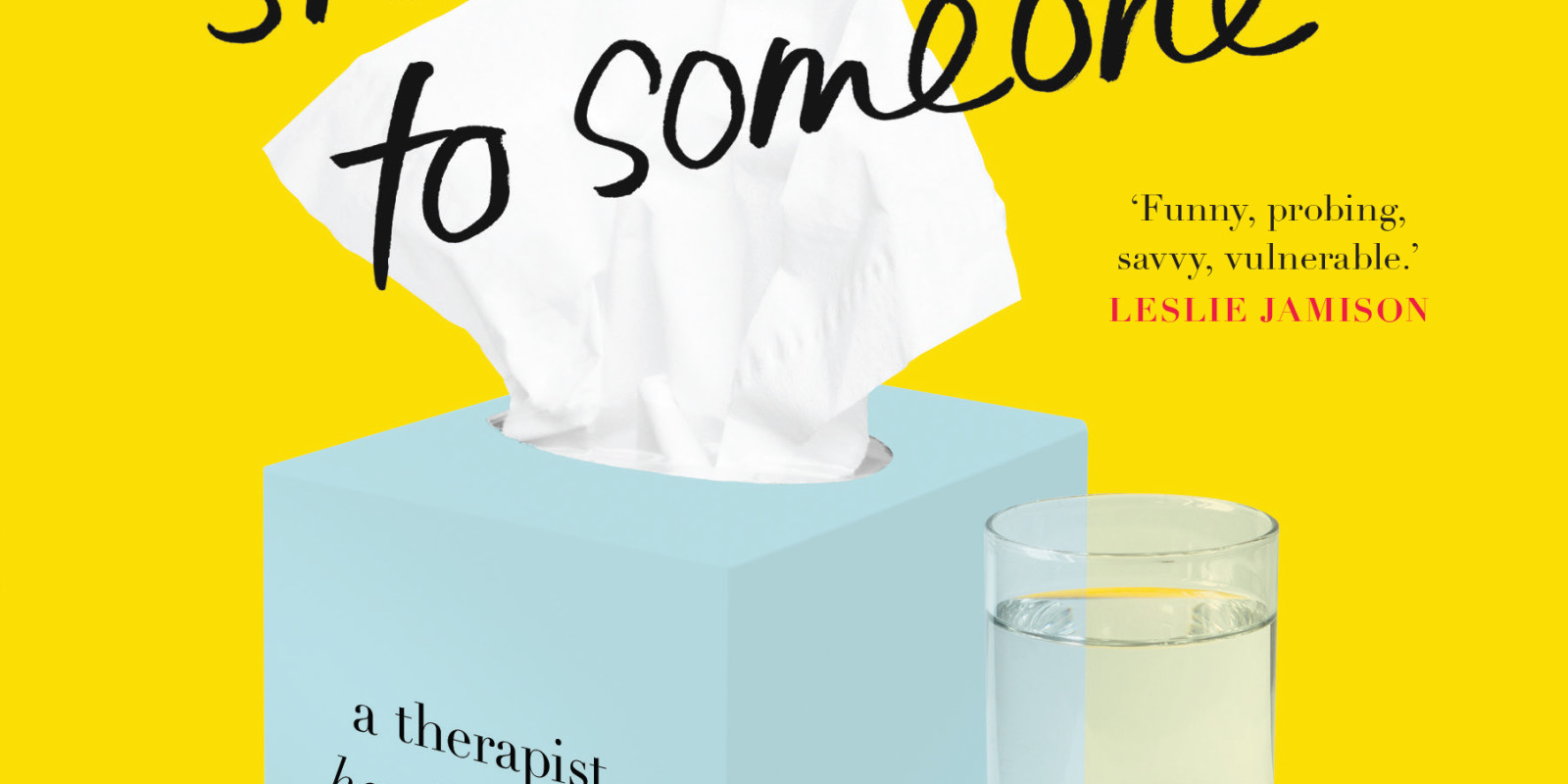

Maybe You Should Talk to Someone

Lori Gottlieb

A little-discussed fact: Therapists go to therapists. We’re required, in fact, to go during training as part of our hours for licensure so that we know firsthand what our future patients will experience. We learn how to accept feedback, tolerate discomfort, become aware of blind spots, and discover the impact of our histories and behaviors on ourselves and others.

But then we get licensed, people come to seek our counsel and . . . we still go to therapy. Not continuously, necessarily, but a majority of us sit on somebody else’s couch at several points during our careers, partly to have a place to talk through the emotional impact of the kind of work we do, but partly because life happens and therapy helps us confront our demons when they pay a visit.

And visit they will, because everyone has demons—big, small, old, new, quiet, loud, whatever. These shared demons are testament to the fact that we aren’t such outliers after all. And it’s with this discovery that we can create a different relationship with our demons, one in which we no longer try to reason our way out of an inconvenient inner voice or numb our feellngs with distractions like too much wine or food or hours spent surfing the internet (an activity my colleague calls “the most effective short-term nonprescription painkiller”).

One of the most important steps in therapy is helping people take responsibility for their current predicaments, because once they realize that they can (and must) construct their own lives, they’re free to generate change. Often, though, people carry around the belief that the majority of their problems are circumstantial or situational—which is to say, external. And if the problems are caused by everyone and everything else, by stuff out there, why should they bother to change themselves? Even if they decide to do things differently, won’t the rest of the world still be the same?

It’s a reasonable argument. But that’s not how life generally works.

Remember Sartre’s famous line “Hell is other people”? It’s true—the world is filled with difficult people (or, as John would have it, “idiots”). I’ll bet you could name five truly difficult people off the top of your head right now—some you assiduously avoid, others you would assiduously avoid if they didn’t share your last name. But sometimes—more often than we tend to realize —those difficult people are us.

That’s right —sometimes hell is us.

Sometimes we are the cause of our difficulties. And if we can step out of our own way, something astonishing happens.

A therapist will hold up a mirror to patients, but patients will also hold up a mirror to their therapists. Therapy is far from one-sided; it happens in a parallel process. Every day, our patients are opening up questions that we have to think about for ourselves. If they can see themselves more clearly through our reflections, we can see ourselves more clearly through theirs. This happens to therapists when we’re providing therapy, and it happens to our own therapists too. We are mirrors reflecting mirrors reflecting mirrors, showing one another what we can’t yet see.