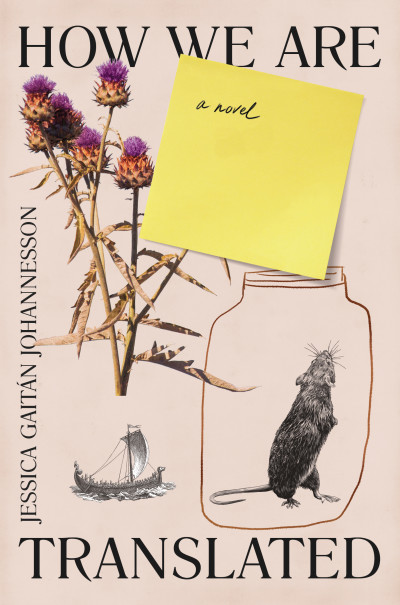

Q&A with Jessica Gaitán Johannesson, debut author of How We Are Translated

Jessica Gaitán Johannesson grew up speaking Spanish and Swedish and currently lives primarily in English. She’s an activist working for climate justice and lives in Bath, England, working for independent bookshop Mr B's Emporium. We asked her a few questions about her debut novel, How We Are Translated.

What inspired How We Are Translated?

I think it came out of the stuff I’ve always tried to work through, to do with holding different selves in different places and languages, and what that means in terms of understanding someone else. This isn’t only just between people who love each other and live together, but moments of intimacy between strangers. I’ve also worked in places where culture, and language, are commercialised to the point where it becomes totally bizarre, like certain museums and tourist attractions. That made me interested in the difference between celebrating culture, and preserving some ideal version of it, as well as the many and subtle ways in which people are forced to prove themselves worthy of being welcomed. The museum where Kristin works came out of that.

Do you identify with Kristin? How similar is your own story to hers?

Our stories are similar in certain ways which are quite superficial, speaking Swedish, choosing Scotland as an adopted home, being in a multilingual relationship. I grew up with two languages, though, from the very beginning. I can’t remember not having that, which I think in itself makes us very different. In some ways, there’s more of me in Ciaran, her partner I find it very easy to get into something and become slightly obsessed.

Exploring distance to both characters was a big part of writing and re-writing the book. The voice is Kristin’s so that meant finding other ways to get to Ciaran and find out why he was reacting to change in the way he does.

You're a committed climate activist — how much did your activism shape the novel?

Hugely, but in an odd way, like a kind of sucker punch from the side. I’d already finished the first draft when the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) report of Oct 2018 came out, which for both myself and my partner was the moment the idea of the future itself changed. As for a lot of people who, like us, are privileged enough not to feel the physical threat of climate collapse, that report was horrifying and completely disorienting, because it was telling us that the future was already here. We threw ourselves into organising with different organisations. When it was time to go back and edit the book, it felt unfamiliar. I had to look much more closely at what the characters’ fears for the future – and being parents in it - might be. This is a fear which so many young people in this part of the world have now, but which has been a reality for people on the frontline of climate collapse for decades: to not have a future at all.

In the end, I found a new footing in the novel when I started learning more about the fundamental connections between climate justice and migration. I truly believe that we need to change the entire way we look at migration. When people are threatened or unsafe we look for new homes. Even talking about ‘climate refugees’ might not be all that helpful, because climate collapse is leading to threats in so many different ways, such as wars and famines. So, a part of the effort to save as many of us as we can will be about how we look at migrants’ rights. What’s the role of the hostile environment, for example, in which people have to jump through a thousand hoops and prove ourselves ‘useful’ in particular ways in order to reach safety? I was back with these stories about how migration is talked about and made sense of.

How long did it take to write How We Are Translated?

To be honest, I really have no idea. Depending on how you look at it, it could be anywhere from a year to four, because of different versions, and because of working first a full-time job and then down to part-time. I think really it probably took a year. Let’s say a year, stretched out into very many early mornings.

If there was one thing you want readers to take away from the book, what would it be?

I really can’t answer that without getting very cringey. If I read that an author wants me to feel sad after reading their book, and I don’t feel that way, then either I didn’t get the book, or I’ll think the author failed. Either way we’re not really friends anymore. (I’m not saying I want you to feel sad after reading the book, by the way.)

I guess I can say that I feel very strongly about certain things in the book – that they’re really important to me. These are the questions about how we isolate ourselves inside our own lives, caring primarily about what affects our immediate families and friends – especially now (and regardless of Covid) it’s so very easy to isolate and confuse that with long-term safety. It’s natural, but I think we need to keep stretching in the opposite direction. I would much, much rather spend all my time in my flat with my husband than go out and take part in direct actions or keep actively learning from others, to expose myself to such potential difference, but we need to keep strengthening that anti-isolation muscle every day. It will be vital, it is vital.

How We Are Translated

LONGLISTED FOR THE DESMOND ELLIOTT PRIZE

People say ‘I’m sorry’ all the time when it can mean both ‘I’m sorry I hurt you’ and ‘I’m sorry someone else did something I have nothing to do with’. It’s like the English language gave up on trying to find a word for sympathy which wasn’t also the word for guilt.

Swedish immigrant Kristin won’t talk about the Project growing inside her. Her Brazilian-born Scottish boyfriend Ciaran won’t speak English at all; he is trying to immerse himself in a Swedish

språkbad language bath,

to prepare for their future, whatever the fick that means.…