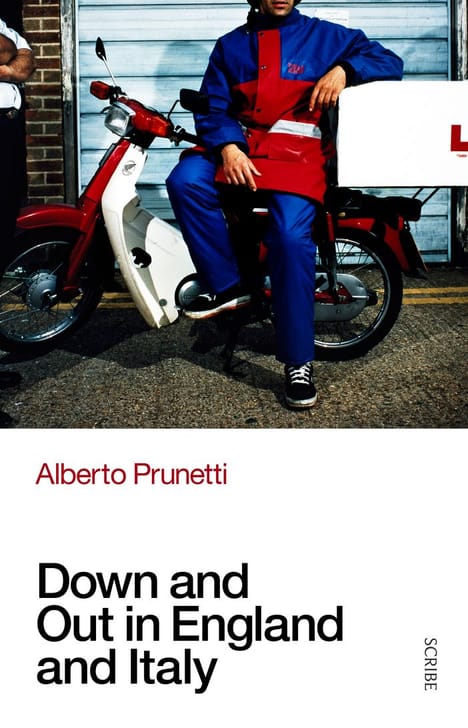

Down and Out in England and Italy

Translated by Elena Pala

Overview

A wry, intelligent, and unputdownable look at class and national identity today.

Alberto Prunetti arrives in the UK, the twenty-something-year-old son of a Tuscan factory worker who has never left home before. With only broken English, his wits, and an obsession with the work of George Orwell to guide him, he sets about looking for a job and navigating his new home.

In between long, hot shifts in pizzerias and cleaning toilets up and down the country, he finds his place among the British precariat. His comrades form a polyglot underclass, among them an ex-addict cook, a cleaner in love with opera, an elderly Shakespearean actor, Turks impersonating Neapolitans to serve pizzas, and a cast of petty criminals ‘resting’ between bigger jobs.

Stuck between a past haunted by Thatcher and a future dominated by Brexit, Down and Out in England and Italy is a hilarious and poignant snapshot of life on the margins in modern-day Britain.

Details

- Format

- Size

- Extent

- ISBN

- RRP

- Pub date

- Rights held

- Other rights

- Paperback

- 216mm x 135mm

- 160 pages

- 9781913348373

- GBP£12.99

- 11 November 2021

- World English

- Gius. Laterza & Figli

Categories

Awards

- Winner of the null Ultima Frontiera Award

- Shortlisted for the null Biella Literature and Industry Prizes

Praise

‘A hallucinatory and savage account of modern working life. Both surreal and instantly recognisable.’

‘Raw, mischievous, funny, and vulgar … engaging.’

About the Author

Alberto Prunetti was born in a Tuscan steel town in 1973. A former pizza chef, cleaner, and handyman, he is also the author of five novels and has translated works by George Orwell, Angela Davis, David Graeber, and many others. Since 2018 he has directed the Working Class books series for the publisher Edizioni Alegre. Down and Out in England and Italy won the Ultima Frontiera Award and was a finalist for the Biella Literature and Industry Prizes.

Translator

Elena Pala is translator whose love of all things language has taken her to many weird and wonderful places. After early years spent shepherding tourists around the Eiffel Tower, and pursuing a PhD in linguistics at Cambridge University, followed by a stint at a busy creative agency in London, she eventually found her calling. Previous translations include The Hummingbird by Sandro Veronesi.