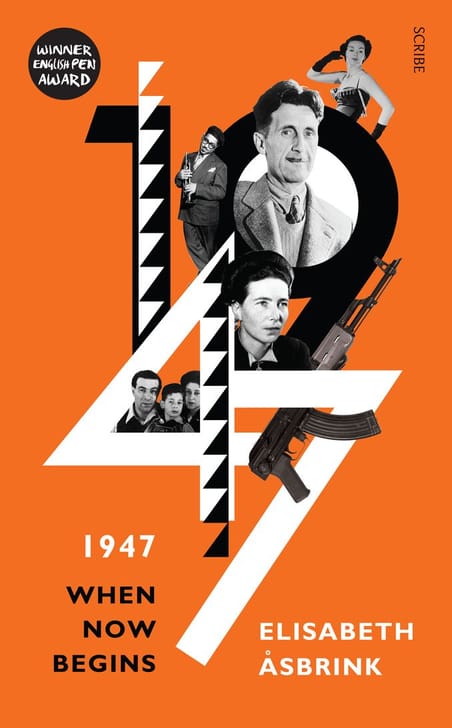

1947:

when now begins

Translated by Fiona Graham

Overview

A Metro book of the year

Interweaving the social, political, and personal, in 1947 Elisabeth Åsbrink chronicles the year that ‘now’ began.

In 1947, production begins of the Kalashnikov, Christian Dior creates the New Look, Simone de Beauvoir writes The Second Sex, the CIA is set up, a clockmaker’s son draws up the plan that remains the goal of jihadists to this day, and a UN Committee is given four months to find a solution to the problem of Palestine.

In 1947, millions of refugees flee across Europe looking for new homes, among them Elisabeth Åsbrink’s father.

In 1947, the forces that will go on to govern all our lives during the next 70 years first make themselves known.

Details

- Format

- Size

- Extent

- ISBN

- RRP

- Pub date

- Hardback

- 210mm x 148mm

- 288 pages

- 9781911344421

- GBP£16.99

- 20 October 2017

Categories

Awards

- Winner of the 2017 English PEN Award

- Longlisted for the 2018 Warwick Prize for Women in Translation

- Longlisted for the 2019 JQ Wingate Prize

Praise

‘[A]n extraordinary achievement.’

‘Extraordinarily inventive and gripping, a uniquely personal account of a single, momentous year.’

About the Author

Translator

Fiona Graham is a British literary translator, editor, and reviewer who has lived in Kenya, Germany, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Nicaragua, and Belgium. Her recent translations include Elisabeth Åsbrink’s 1947: when now begins, an English PEN award-winner longlisted for the Warwick Women in Translation Prize and the JQ Wingate Prize, and Torill Kornfeldt’s The Unnatural Selection of Our Species.